Paleofire ecology in boreal Alaska

Climate and vegetation work synergistically to drive fire activity at centennial and landscape scales

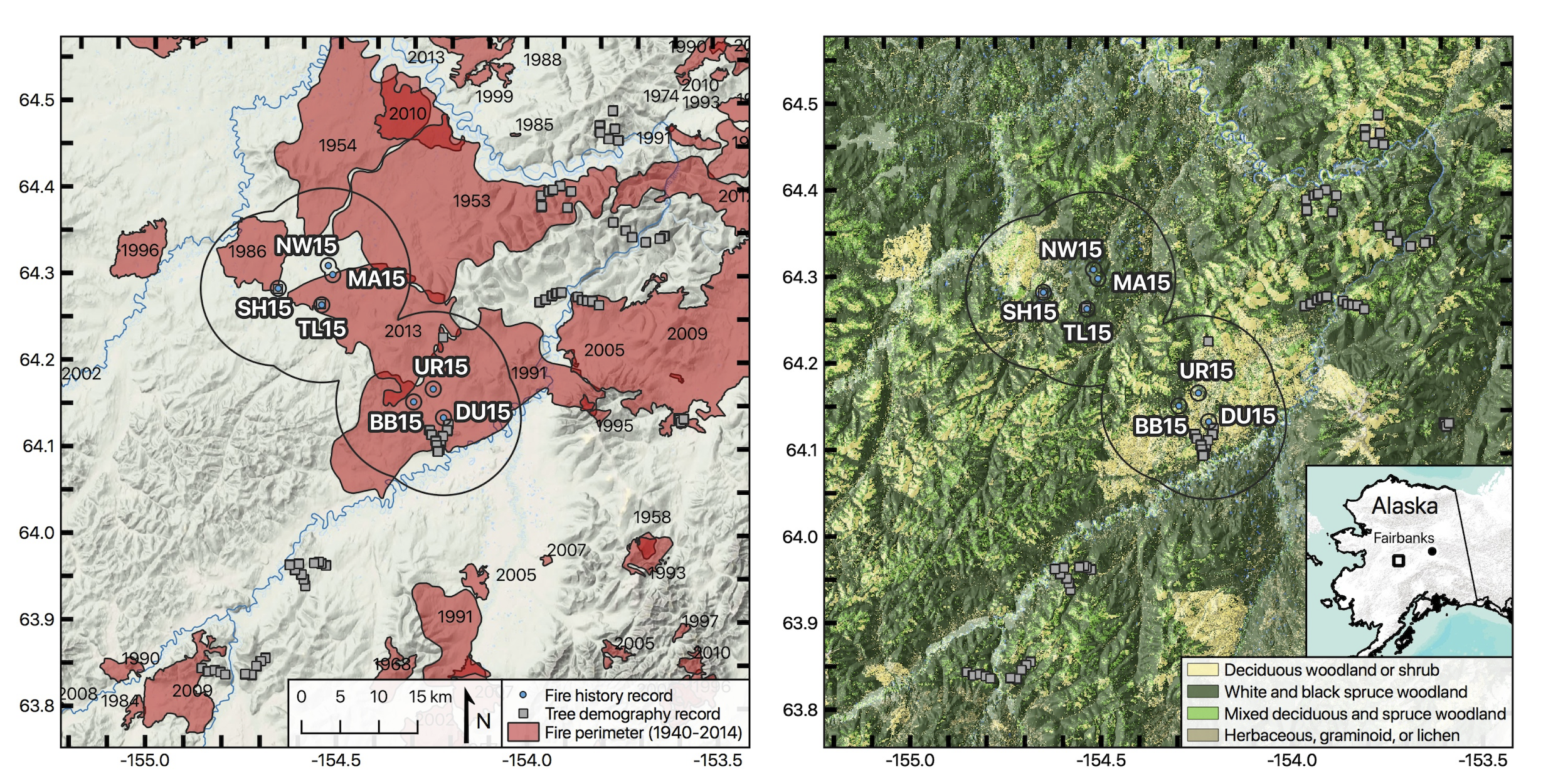

The boreal forest is globally important for its influence on Earth’s energy balance, and its sensitivity to climate change. Ecosystem functioning in boreal forests is shaped by fire activity, so anticipating the impacts of climate change requires understanding the precedence for, and consequences of, climatically induced changes in fire regimes. Long-term records of climate, fire, and vegetation are critical for gaining this understanding. We investigated the relative importance of climate and landscape flammability as drivers of fire activity in boreal forests by developing high-resolution records of fire history, and characterizing their centennial-scale relationships to temperature and vegetation dynamics. We reconstructed the timing of fire activity in interior Alaska, USA, using seven lake-sediment charcoal records spanning CE 1550-2015. We developed individual and composite records of fire activity, and used correlations and qualitative comparisons to assess relationships with existing records of vegetation and climate. Our records document a dynamic relationship between climate and fire. Fire activity and temperature showed stronger coupling after ca. 1900 than in the preceding 350 yr. Biomass burning and temperatures increased concurrently during the second half of the 20th-century, to their highest point in the record. Fire activity followed pulses in black spruce establishment. Fire activity was facilitated by warm temperatures and landscape-scale dominance of highly flammable mature black spruce, with a notable increase in temperature and fire activity during the 21st century. The results suggest that widespread burning at landscape scales is controlled by a combination of climate and vegetation dynamics that together drive flammability.

Download a PDF of the publication in Landscape Ecology

Holocene records of fire activity from across Alaska suggest contemporary fire activity is unprecendented

Boreal forest and tundra biomes are key components of the Earth system because the mobilization of large carbon stocks and changes in energy balance could act as positive feedbacks to ongoing climate change. In Alaska, wildfire is a primary driver of ecosystem structure and function, and a key mechanism coupling high-latitude ecosystems to global climate. Paleoecological records reveal sensitivity of fire regimes to climatic and vegetation change over centennial-millennial time scales, highlighting increased burning concurrent with warming or elevated landscape flammability. To quantify spatiotemporal patterns in fire-regime variability, we synthesized 27 published sediment-charcoal records from four Alaskan ecoregions, and compared patterns to paleoclimate and paleovegetation records. Biomass burning and fire frequency increased significantly in boreal forest ecoregions with the expansion of black spruce, ca. 6-4 thousand years before present (yr BP). Biomass burning also increased during warm periods, particularly in the Yukon Flats ecoregion from ca. 1000-500 yr BP. Increases in biomass burning concurrent with constant fire return intervals suggest increases in average fire severity (i.e., more biomass burning per fire) during warm periods. Results also indicate increases in biomass burning over the last century across much of Alaska that exceed Holocene maxima, providing important context for ongoing change. Our analysis documents the sensitivity of fire activity to broad-scale environmental change, including climate warming and biome-scale shifts in vegetation. The lack of widespread, prolonged fire synchrony suggests regional heterogeneity limited simultaneous fire-regime change across our study areas during the Holocene. This finding implies broad-scale resilience of the boreal forest to extensive fire activity, but does not preclude novel responses to 21-century changes. If projected increases in fire activity over the 21st century are realized, they would be unprecedented in the context of the last 8,000 years or more.